Of Tales, Tortoises and Taxonomies

The Cloud embodies and enacts all the conflicts of understanding we encounter in our attempts to understand the more-than-human world. It shows us, every day, that an information regime – a way of thinking and classifying the world – which depends upon fixed data and unbreakable categories, on conclusions over process, ends over means, on biases and assumptions rather than the evidence of our own lives, is antithetical to society, humankind and life itself. No schema is ever complete, no taxonomy ever finished – and that’s fine, providing the systems we put in place for interpreting and applying those schemas are open, transparent, comprehensible and renegotiable.

– James Bridle, in: Ways of Being. Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence. Penguin Books 2023

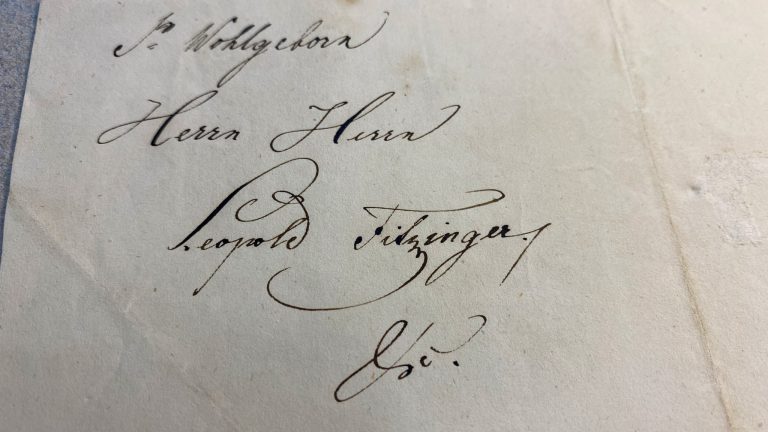

The correspondence between Leopold Joseph Fitzinger and other European natural scientists of the mid 1800s occupies a crossroads in this artistic research project. By accessing these letters, I am unlocking insights that will inform the narration of a fact/fiction short film concerned with classification and intelligence: how systems of knowledge order the world, and how those systems in turn exert power over the beings they seek to describe.

Across my films and artworks, I have long investigated the human condition and agency in the networked age, interrogating narratives of “progress through technology” since the 1990s. In more recent works such as ALGO-RHYTHM, AICONIC, and Capital pAIn, I have critically examined the societal impact of artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-making. These projects address what might be described as a contested regime of automated governance, in which corporate, black-boxed systems categorise and predict human behaviour based on large-scale online data collection. Practices such as micro-targeting—designed to influence opinions and choices—and social scoring—used to determine access to education, housing, or financial services—rely on reductive models of personality traits. These models can be traced genealogically to nineteenth-century pseudo-scientific projects such as eugenics, most notably articulated by Francis Galton.

This historical lineage is not incidental. The early nineteenth century was also a period of intense activity within the natural sciences, marked by ambitious efforts to produce comprehensive taxonomies of the natural world. The desire to assign organisms a fixed place within an internationally shared system of order flourished, and Leopold Joseph Fitzinger played a significant role in this endeavour. Born in Vienna, Fitzinger began collecting insects and shells at an early age and went on to study mineralogy, chemistry, zoology, and botany under Joseph Franz Jacquin. At the age of fifteen, he began volunteering at the Naturalienkabinett, the precursor to today’s Naturhistorische Museum Wien, where he contributed for decades to the collections of fish, amphibians, and reptiles. In 1844 he was appointed Custosadjunkt at the museum.

Fitzinger is best known for his herpetological publications, particularly Neue Classification der Reptilien nach ihren natürlichen Verwandtschaften (1826), in which he proposed a new system for classifying reptiles according to their perceived natural affinities. In the introduction, Fitzinger reflects on the inherent difficulty of classification as the search for “a system in which natural objects are arranged according to their greatest similarity, according to their natural relationships […] faces its greatest difficulty in the correct selection of characteristics and in determining their proper rank. How easily one may fall into artificial methods in this process is known to anyone who has engaged in natural classification.”

This admission identifies a central issue still valid in the context of today’s practices of classification: how does one select the attributes by which categories are formed, and what authority underpins those selections? What consequences follow from such choices for how organisms are understood—and, in the case of humans, what power structures are introduced or reinforced? While classification can enable knowledge and care, it also carries the potential for harm. When applied to humans at scale, in opaque and unaccountable ways, under the banner of technological “progress” these practices become deeply unsettling. They shape not only how individuals are governed, but how we come to understand ourselves.

Another strand of my research intersects with these questions through lived, interspecies experience. My family has cohabited with Tschili, a marginated tortoise (Testudo marginata), since the 1970s. We encountered him—today I would say we “met” him—with a life-threatening neck injury on a rocky mountainside near Argos, Greece. We took him in to care for him, and at the end of our stay my parents, in the unreflective spirit of the time, allowed me to bring him back with us to Vienna. A large, strong-willed male, Tschili has always seemed ageless: approximately one hundred years old when we met him fifty years ago, and perhaps still so today.

As a proponent of eco-philosophical and More-than-Human perspectives, articulated by thinkers such as David Abram, I began a project that takes seriously the question of intelligence beyond the human (particularly in response to the narrow and instrumentalised use of the term within AI discourse). The project departs from a deceptively simple question, asked from Tschili’s perspective: “Who am I in relation to you?”

Fitzinger was not the first to describe the marginated tortoise, but his Neue Classificationen, published exactly two hundred years ago, provided a framework of genera and subgenera that continues to resonate within contemporary taxonomic practice. This continuity foregrounds a broader question that underlies my research: how historical systems of classification persist, mutate, and reappear within modern technologies of intelligence and governance—and how these systems mediate our relationships not only with other humans, but with the more-than-human world.

Image credits

Letter addressed to Leopold Fitzinger, herpetologist at the k.k. Hof-Naturalien-Kabinet (precursor of today’s Natural History Museum, Vienna) written by botanist Johan Georg Bill (1844). with permission of UCL Special Collections, Lord Odo Russel collection

Room of Reptiles, Natural History Museum, Vienna